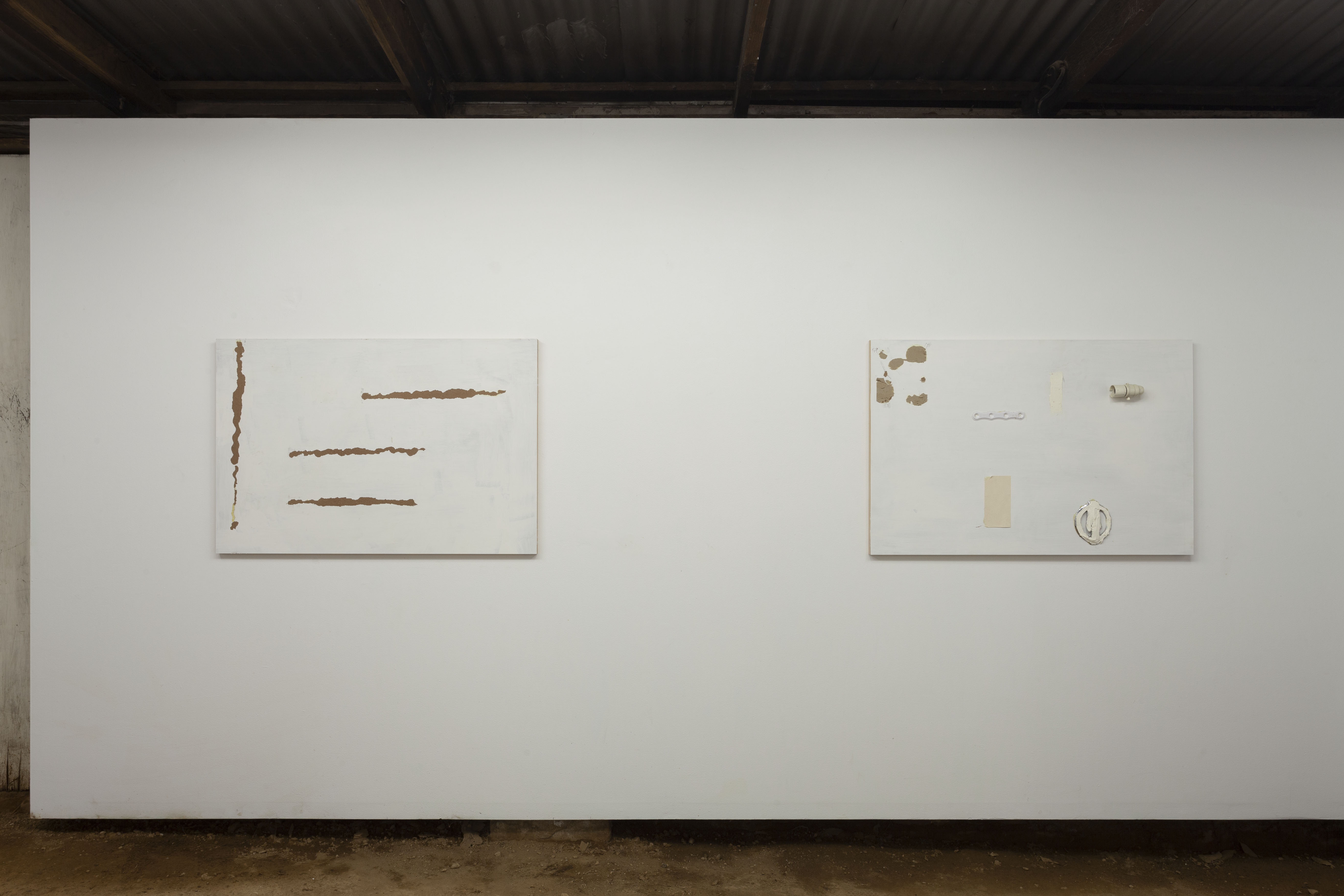

Untitled (1), 2019. Ski goggles, hair roller pins, bottle cap, cigarette packets, pencil, Panadol dispensary pen, Kwik grip, acrylic paint

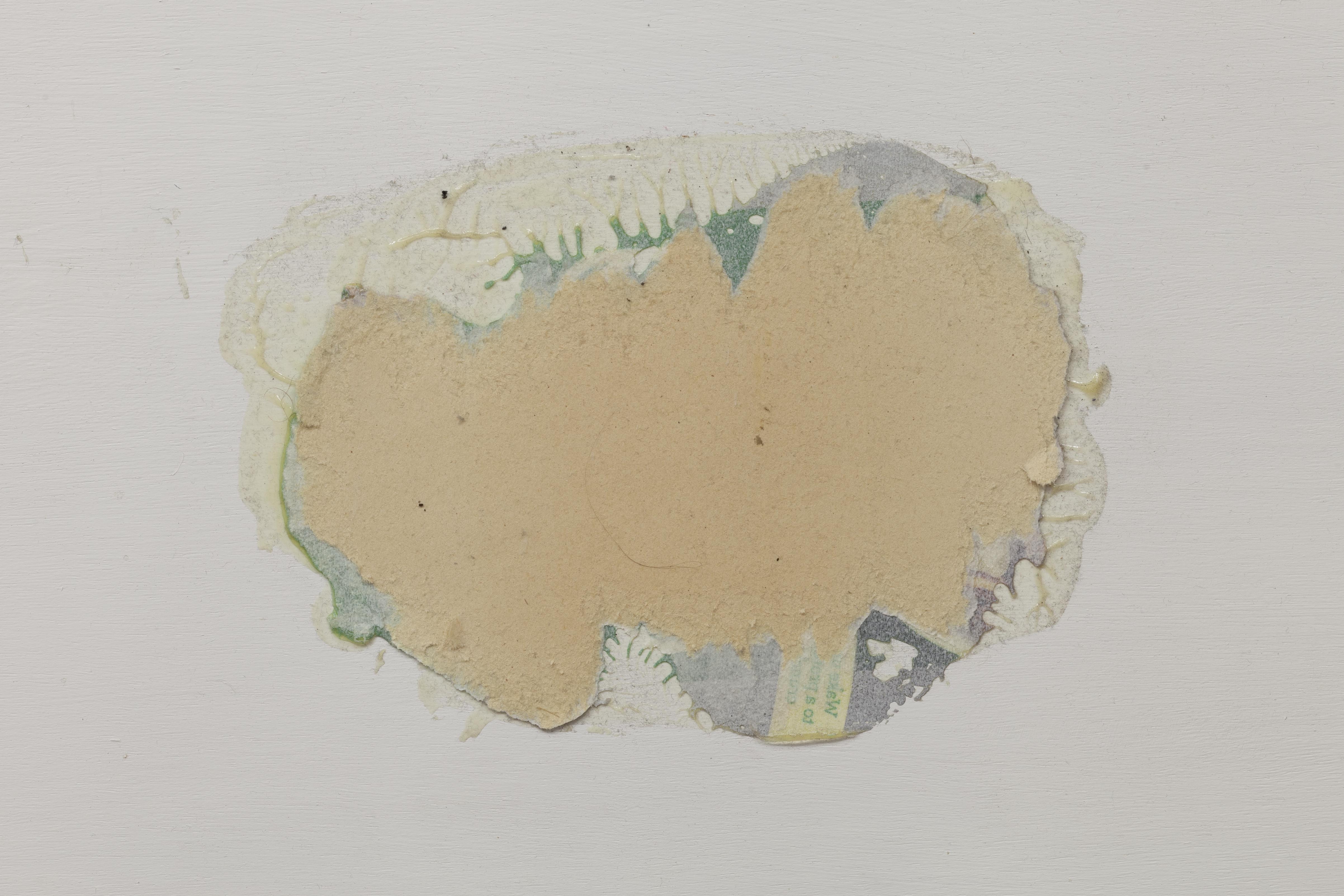

Untitled (2), 2019–22. Door mat, aluminium foil, PVA, Kwik grip, acrylic paint

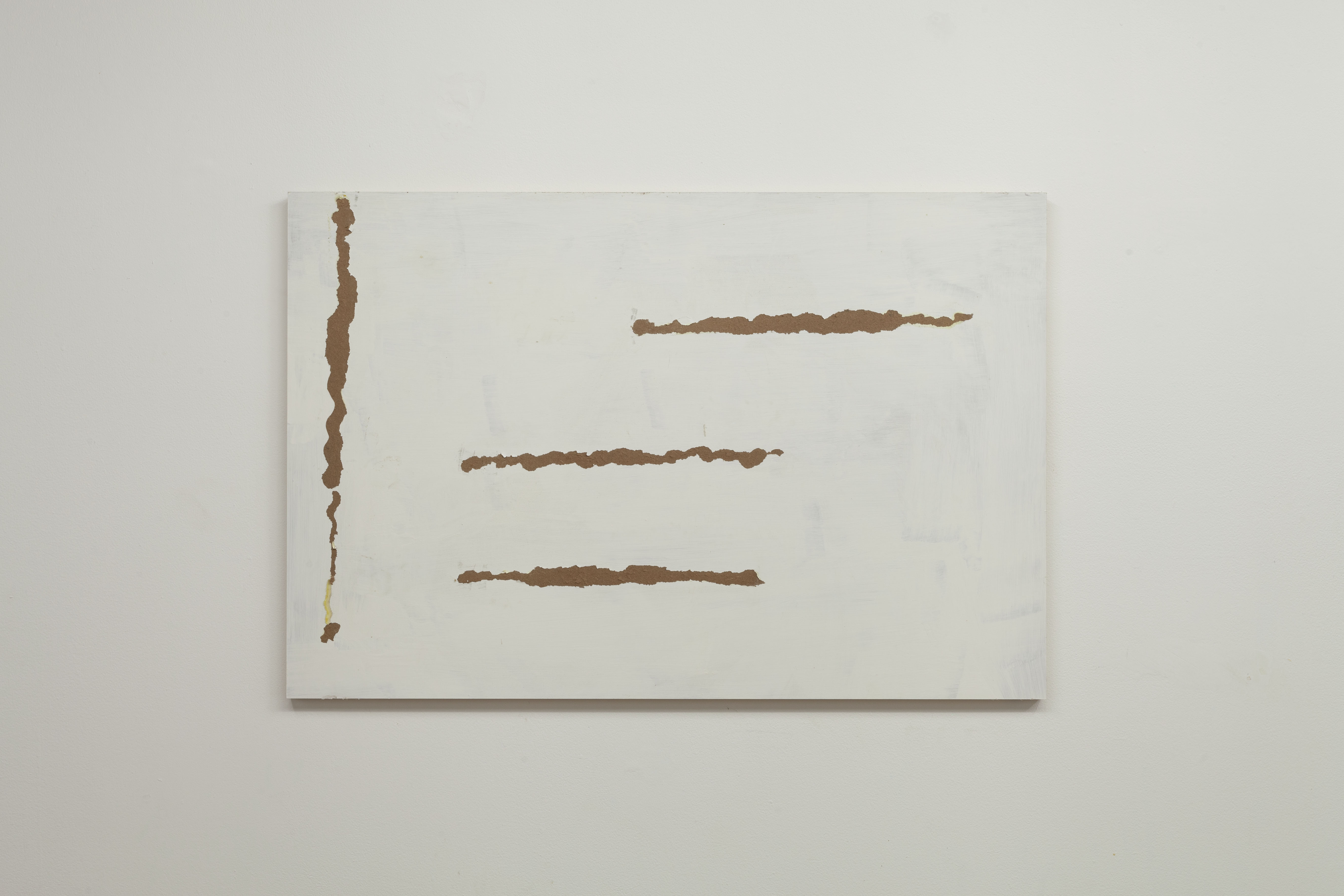

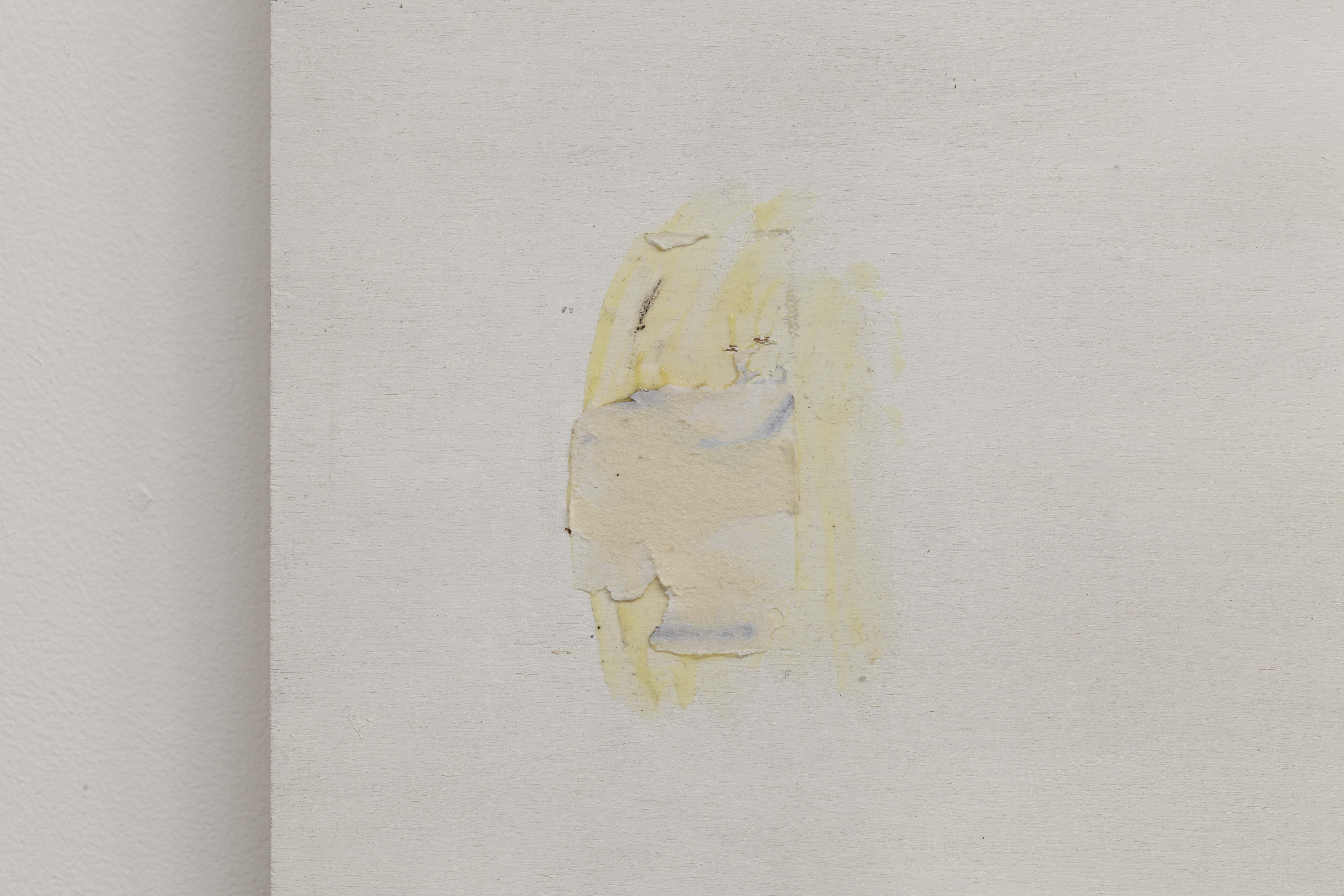

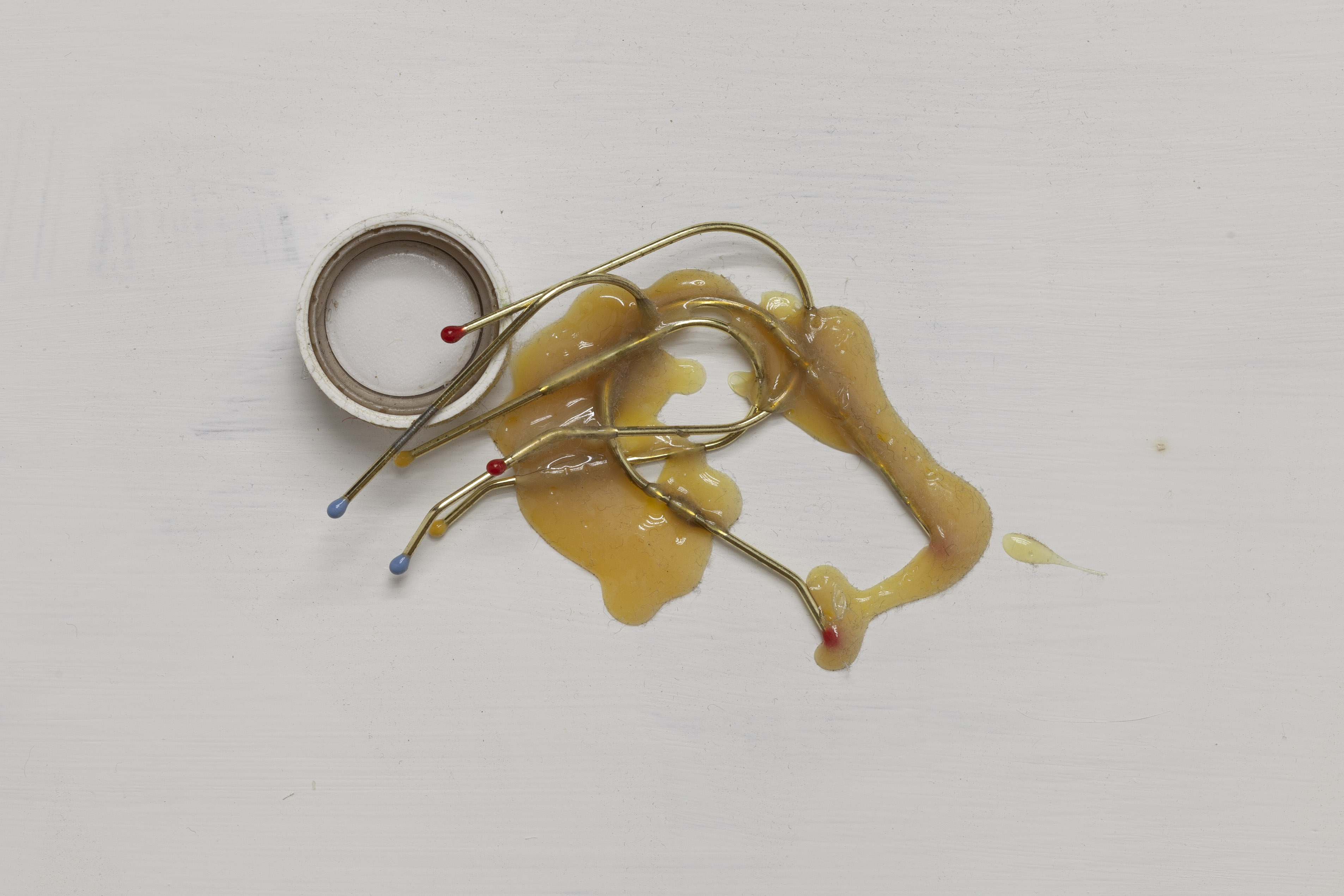

Untitled (3), 2019–22. Acrylic paint, Kwik Grip

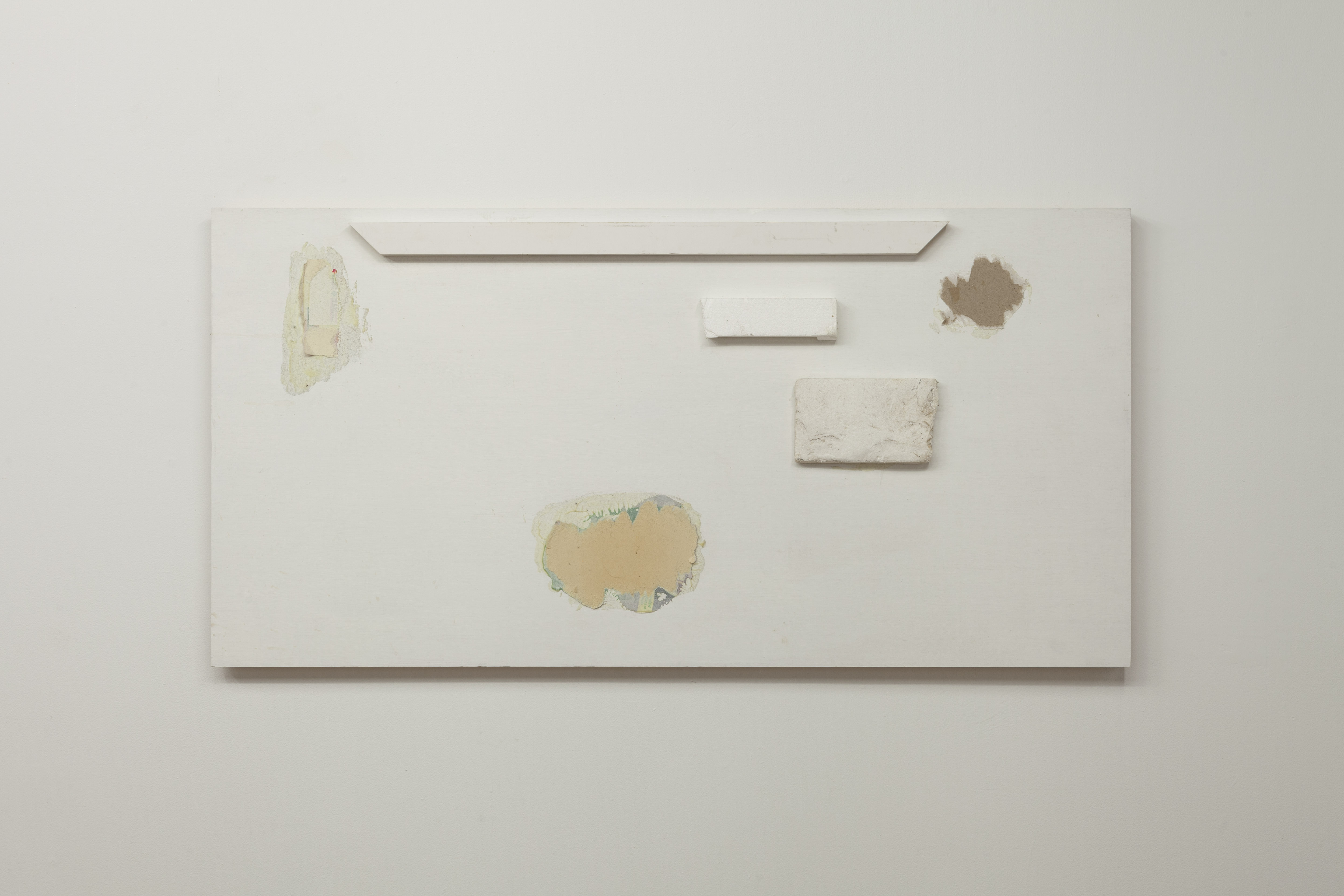

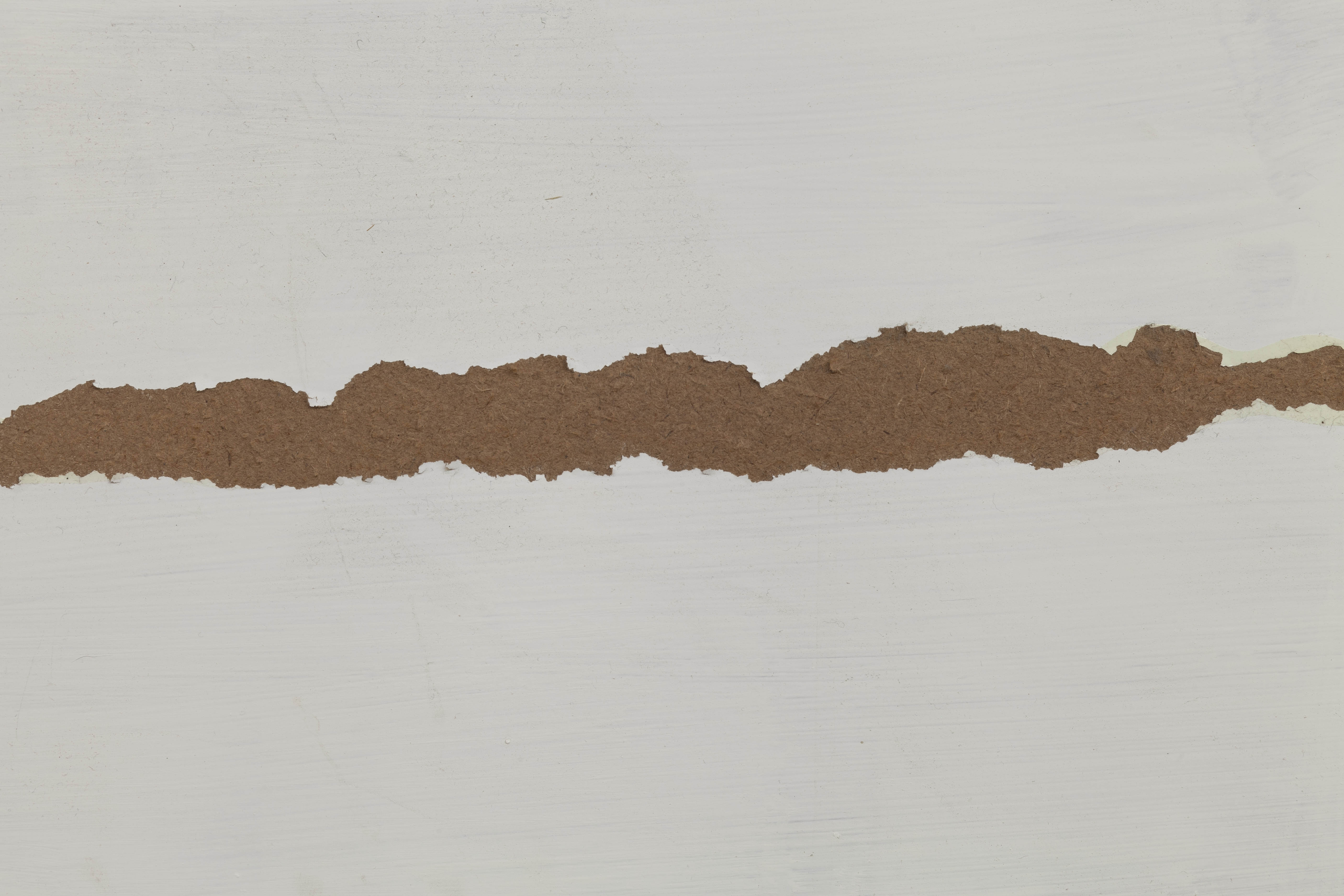

Untitled (4), 2019–22. Primed MDF, styrofoam, cardboard, polystyrene, Kwik grip, acrylic paint

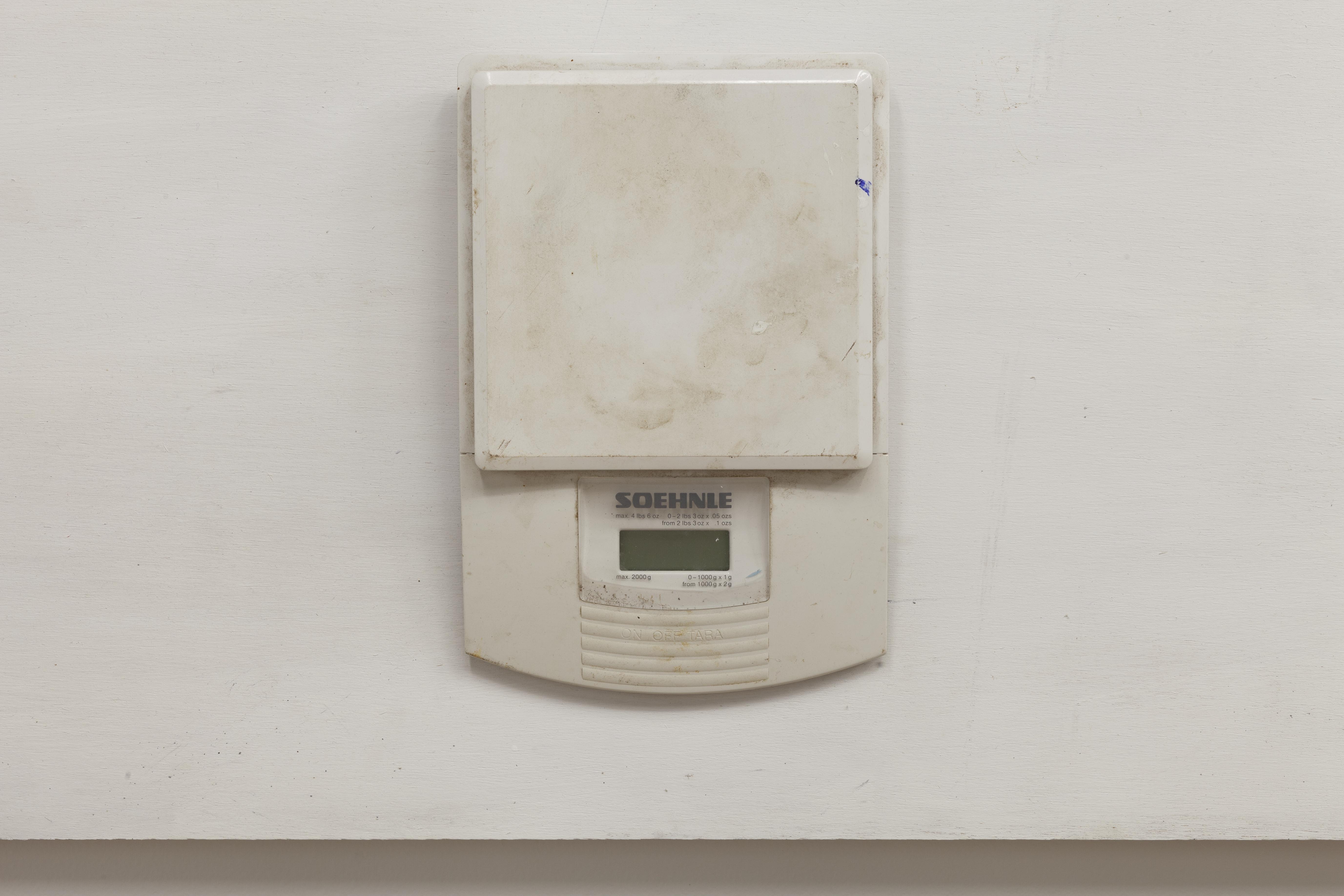

Untitled (5), 2019–22. Electronic scales, cardboard, Kwik grip, acrylic paint

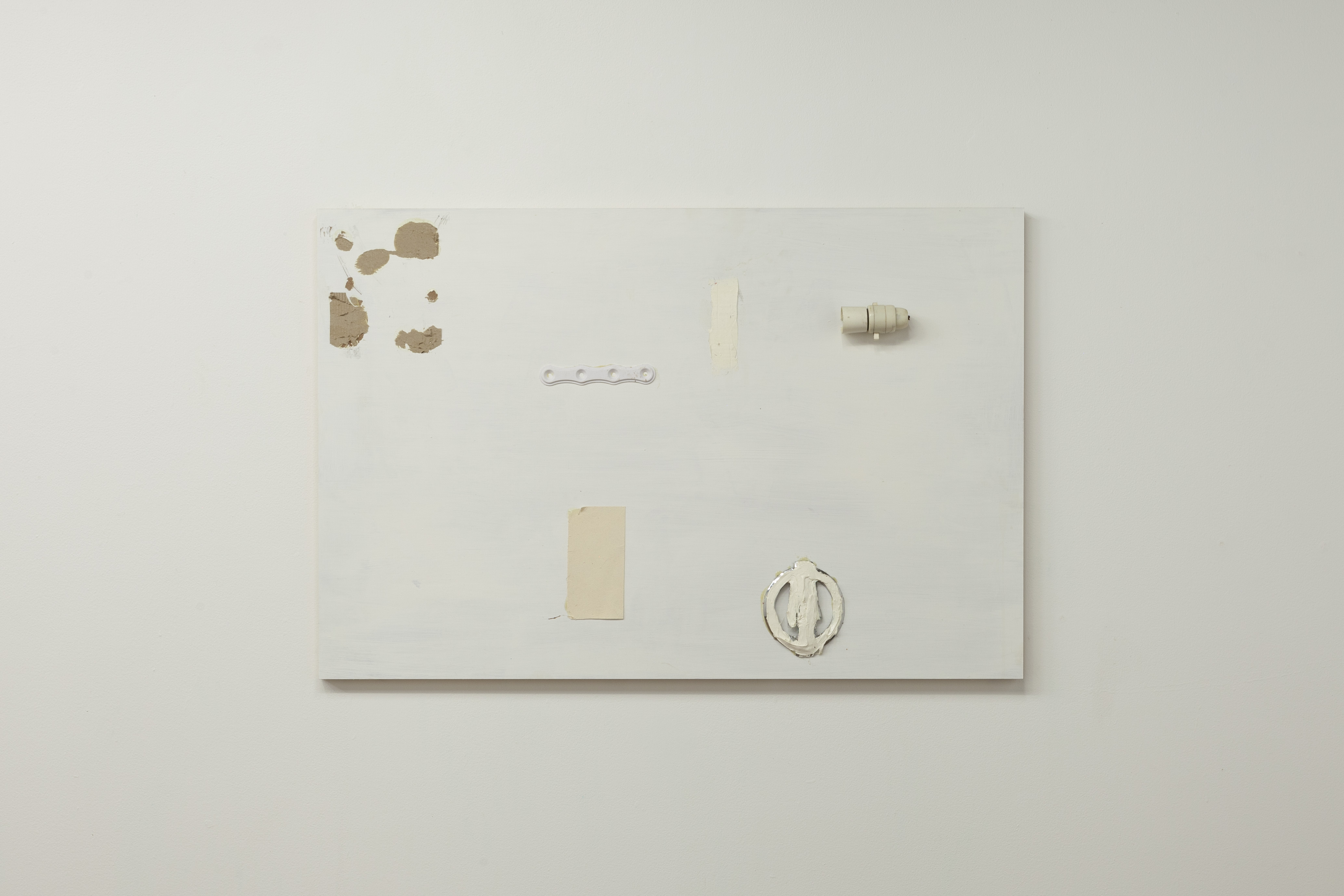

Untitled (6), 2019–22. Silicon covered car badge, light socket, plastic, paper, cardboard, silicon, cardboard, Kwik grip, acrylic paint

Trash art is nothing new, of course. As the opposite of the rarified art object, trash is an obvious target for an artist’s rarifying hand, a “challenge” to turn non-art (whatever that is) into art (whatever that is). There’s little point in defining either of those states, but trash art begs the question of the transformation itself. Garbage is refuse, that which is refused, something that one wants to get rid of because it holds no value. Rinds and wrappers are thrown into bags that are thrown into piles that are thrown into garbage trucks and crushed in compactors, piled, burned, buried, or otherwise put somewhere where we don’t have to think about it anymore. We give some consideration to most things we handle in our daily life; a plate or a computer serves a purpose so we’d rather they didn’t break and stop doing the thing they do, but we don’t care about trash so it accumulates and churns haphazardly. Almost everything affords itself some attention, but trash is defined by the lack of consideration given to it. Art, on the other hand, is the prime object of attention, brought into being by the artist’s attentiveness and only useful as a viewer’s object of contemplation.

So, art gets attention and trash does not. Trash art, then, is paying attention to trash. This usually takes the form of something like Robert Bittenbender’s work, assembling detritus into a dense Gothic sci-fi horror film set, or, really, an art world version of Nick Blinko or Jhonen Vasquez’s punk/emo exaggerated back patch and safety pin style. In basic terms, the process from trash non-art to trash art consists of aestheticizing, imposing a style onto found materials, or, in the absence of style, a conceptual justification to suggest that “this pile of trash is not simply a pile of trash.” Barbara T. Smith, for instance, had a recent exhibition at Andrew Kreps Gallery consisting of works from the 70s that she used as objects of worship in a durational performance. I thought the work was terrible because it looked like an affected presentation of what was still just garbage. Maybe I would have taken it differently if I had seen the performances, or if it was the 70s, but from my perspective she had asserted an imbuement of meaning on the objects without putting in the effort to convince her audience that this supposed religious ceremony wasn’t entirely arbitrary. The arbitrariness is less an issue than it is that that arbitrariness is unintentional; the artist’s attention to the work fails to convince the viewer’s attention. But whether the artist’s imposition on the trash used in the artwork is aesthetic or conceptual the gesture is fundamentally one of ideology, where the artist’s labor implies a stylistic belief or a value judgment regarding what can give value to worthless trash, and this is precisely what Guzzler’s Addled Art does not do.

Rather than elevating trash to the level of art, Addled Art seeks to reduce art to the level of trash. This may sound like a sneering joke of an aspiration, and it may be, but it is not just that. Miscellaneous found and household objects are glued to MDF boards with a level of attention just above carelessness (they had to look where they were gluing, after all), which may have something to do with irony, but rather than an unserious joke the goal is a serious negation of the conventional process of trash art, and of art in general: to impose a perspective. Now, naturally, refusing to take a perspective is not the absence of perspective, but the consequence of this approach is that the objects in the works are not fully incorporated into the idea of the artwork, the style, the “vibe,” the concept, etc. A streak of house paint does not become a painterly line that implies a represented object or perspective, it stays a streak of paint on canvas, or better yet, is stuck between the alternatives of being an independent object and a synthesized element of an artwork. The work is uncertain with itself, sick at the unease of making, unsure if it’s worth the trouble to make a painting or just look at the junk sitting on your kitchen counter and call it a day.

The result is, less than obviously, something remarkable: an unresolved position of art, a confrontational non-art gesture in an era where every non-artistic move is already accepted as art by virtue of its funding institutions. The art world learned a trick a decade or two ago where they could immediately negate any subversive art by clapping at it, smiling and nodding and mumbling, “yes, Andrea Fraser, you are so right, we, the moneyed predators, are so bad, but the radiant flame of your artistic purity has absolved us,” which sullies the purity of her critique by complicity. Guzzler isn’t in the center of the art world, though, they’re not even in Melbourne, they’re in the suburbs, they have a dirt floor. They are cleansed of the art world’s sanctimonious purity by freeing themselves from art’s entire system, and at the same time are placed in the freefall of art’s meaninglessness, because why would anyone in New York make art if not to get rich and famous? This reflects Addled Art itself: a New York artist wants to stylize and transform trash to art because that is what is expected of them as a career New York artist who wants to please their audience, but in Rosanna, Victoria, Australia, there’s no such reason to do anything with the trash unless you feel like it. And if you just feel like it, then you can leave the trash as it is, because maybe what you like about trash is that it’s trash. And that trash is real, unlike the art world’s system of postures that first and foremost signify, no matter what anyone might say, the desire to signify for the sake of selling trash to dumb rich people.

—Sean Tatol

Addled Art 2, 20–29 May 2022